Memory is a complex perception

How does memory work? Why does it get confused in trauma? When trying to recover from overwhelming experiences it can be helpful to understand how memory works, particularly how memories are related to feelings in the body.

There are folklore phrases such as ‘muscle memory’ and ‘cellular memory’ that can be very useful but need to be applied carefully. They speak to the importance of information stored in the body. However it is essential to understand that for the information to be available to our awareness, our brain needs to be involved in processing the patterns of information flow happening in the body. Where the information is processed – in the primitive brain (unconscious) or in the neocortex (conscious) – determines whether or not the memory is explicit.

I have a favourite old pair of jeans right now, some holes are on the second round of stitching. The wrinkles and folds in the material are a memory of sorts, the jeans mould to my body like no other pair of trousers. The fascia researcher Gil Hedley (2005) talks about fascia as ‘fuzz’. The fuzz accumulates and represents time. A certain stickiness and alignment of the fibres in the tissues holds the body in habitual ways, just like the wrinkles in my jeans.

Imagine a small child being shouted out by her father. Her shoulders tense, her neck tightens and there is a surge of fear related hormones and activity in the body. If this happens continuously the pattern of ‘shoulders tense and neck tight’ becomes a ingrained ‘action pattern’ (Kozlowska et al 2015).

Now imagine 30 years later. The girl is now a woman and she is feeling stressed. Maybe she tries a yoga class, gets a massage, does some talking therapy or tries Trauma Releasing Exercises (TRE). Feeling safe and grounded in the novel environment, it is possible the tissues in her neck begin to express long held contractions and tightness. A shape in her body emerges, similar to the pattern generated when she got shouted at.

From feeling safe, her system may suddenly shift into feelings of unease, some stress hormones may be secreted, her posture may go to the familiar ‘shoulders tense and neck tight’. She may even go home that night and think and dream about her about her father. Sometimes these fragments can become intrusive flashbacks.

Explicit versus implicit memory

The changes that happened in the body may or may not be fully integrated into cognition, but something is happening. A memory is being expressed. The ‘muscle memory’ is the tension and tone in the tensegrity of the neck (Ingber 2008). The ‘cellular memory’ is cellular membrane receptors that grew to be sensitive to the all the stress hormones, immune system signalling and inflammatory chemicals secreted in the fear response (Damasio and Carvalho 2013). The ‘action patterns’ are simple, default movement schemas held in the old primitive brain (Kozlowska et al 2015).

The brain sense changes in tissue tension and the cellular chemical milieu. Only with the whole brain involved do we have perceptions, emotions, memories and thoughts generated in awareness (Quiroga 2017).

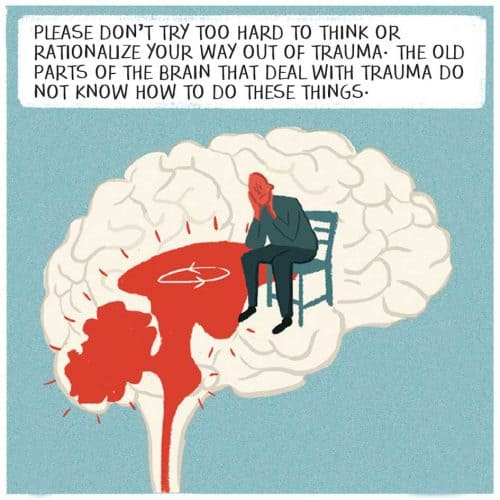

Instead of explicit memories (memories with a timeline and activation in the neocortex) we often only have implicit memories (fragments with an emotional charge, Rothschild 2000). With implicit memories the activation is chiefly in the primitive brain (brain stem, cerebellum and limbic system). The woman becomes scared around sensations in her neck, but she does not really know why she is getting upset.

Implicit memories are coded very simply in the primitive brain. Often they are without a context. Our threat detection systems (LeDoux 2015) hold lots of symbolic representations of threat (‘neck tight’ is a ‘tag’ coupled with fear). The threat detection systems will trigger ‘defense cascades’ (Kozlowska et al 2015) if they sense danger in the incoming information stream.

If the neocortex gets involved then we will have explicit memory – we can pull in associated events and a timeline to contextualise the flow of information. Explicit memories usually only emerge into awareness after the body has changed. In the optimum situation, the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex should help the woman say ‘Your dad shouted way too much, but it was 30 years ago’. But stress makes everything go too quick and tends to inhibit the hippocampus and neocortex.

Explicit memories are not essential when trying regulate the defense cascade. It is important to honour the memories and stories that appear, however try not to not get distracted by them and do not put too much energy in trying to make the narrative come together. Do go really slowly and keep orienting to feeling safe in your body and your environment in the present time. Tell yourself ‘The danger is not happening now’, even if your primitive brain is screaming at you to run, jump, fight or shutdown.

Following Dr David Berceli, founder of TRE, I am fond of saying ‘You do not need to remember or do not need to understand to heal trauma’. The goal is to feel safe right now and not get activated by the ‘tissue memories’, ‘cellular memories’ and ‘action patterns’. We can learn to be more than old protective patterns that are seeking to take over.

Recognising early signs of distress

When working with trauma it is important to note the surges and changes in the rhythmic activity of the body as implicit memories occur. There are some great early warning signals that too much is happening too soon. Kozlowska et al (2015) list some early signs of mobilising (‘fight-or-flight’); changes in breath, furrowing of the eyebrows, the tensing of the jaw, or the clenching of a fist, narrowing of the range of attention. For early signs of immobilising (‘freeze’ and ‘dissociation’) they list; visual blurring, sweating, nausea, warmth, light-headedness, and fatigue.

My favourite signs (Haines 2016) are anything going too quick; thoughts, sensations or emotions that cannot be integrated into the present moment and anything going too slow; spacey, floaty, absence, hard to make eye contact, numbness or tingling or loss of body awareness.

Dry mouth, distorted hands or feet, absent belly, cold hands and a sense of disappearing are all good signs to put the brakes on and become more grounded, whatever process is being expressed. David Berceli (2008) teaches avoiding ‘freezing, flooding or dissociation’, these are signs that too much arousal is occurring to integrate in the present moment.

When we are more grounded we can then help find the right pace of change so we can self-regulate. Sometimes the presence of a safe other person is necessary to lead us to co-regulate, so we can learn to self-regulate (Ndefo 2015). Context and environment will change how memories are expressed, for good or for ill. The primitive brain does not do words and concepts very well, but will respond to safety, touch, presence and going slow.

Summary

- Information is stored in the tissues and cells of the body. We frequently only experience fragments of implicit memories.

- Memories are stored inside people and people are inside families, society and cultures. Remembering is a complex perception that depends on context. Quiroga 2017 states ‘perception and memory are based on similar principles’ and ‘Our memories are dynamically recreated with each recall.’

- The threat detection systems in the primitive brain can be activated as the body changes. The stimulus could be a safe, novel situation or ongoing stress or an unknown symbol.

- The primitive brain does not do words and concepts very well, but will respond to safety, touch and presence.

- If we can support change in the body, and regulate arousal, we can change activation without needing to understand or remember the trauma event. The goal is to uncouple the charge of the defense cascade from the sensations of the implicit memory.

References

- Berceli D (2008) The Revolutionary Trauma Release Process. Transcend Your Toughest Times. Vancouver: Namaste Publishing.

- Damasio A and Carvalho GB (2013) The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, Vol 14, February 2013, 143.

- Haines S (2016) Trauma Is Really Strange. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Hedley G (2005) The Integral Anatomy Series. 4 Vol DVD set. Integral Anatomy Productions, LLC, 430 Westwood Avenue, Westwood, NJ 07675, USA (or check ‘The Fuzz Speech’ on YouTube).

- Ingber DE (2008) Tensegrity and mechanotransduction. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 12, 198–200.

- Kozlowska K, Walker P, McLean L, and Carrive P (2015) Fear and the Defense Cascade: Clinical Implications and Management. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015 Jul; 23(4): 263–287.

- LeDoux JE (2015) The Amygdala Is NOT the Brain’s Fear Center. psychologytoday.com http://bit.ly/ledoux-no-fear-center Accessed 2015-09-01

- Ndefo N (2015) Personal communication. ‘Sometimes we have to co-regulate before we can self-regulate’.

- Quiroga RQ (2017) The Forgetting Machine: Memory, Perception, and the “Jennifer Aniston Neuron”. Dallas: BenBella Books Inc.

- Rothschild B (2000) The Body Remembers – The Psychophysiology of Trauma and Trauma Treatment. London: W.W. Norton.